Music Heard, Music Seen: Concert Posters and Allied Musical Diplomacies in Post-War Austria[1]

By Alexander Golovlev

Interactions of music with the visual arts represent a promising field of studies within cultural, media and visual history. Indeed, its perspectives for different avenues of historical inquiry are considerable, and visual aspects of music have significant potential to contribute to scholarly understanding of the interplay between sounds, images, and perceptions. Music’s interconnections with state power, representation strategies have gained ascendance within sociology and international relations.[2] Construction, transmission, reception and interpretation of music’s nonverbal messages have led its study outside the ivory tower of the musicological profession. Likewise, investigation of multifaceted patterns of interactions between individual, social and state actors unites studies of acoustic and visual cultures within the contextual agenda set by new cultural history.

Images possessed a power of their own, aiming to create and strengthen desired consumption and habitus patterns or to convey messages of power and hierarchy. Within modern and contemporary visual culture (W.J.T. Mitchell, Nicholas Mirzoeff among others), and concomitantly with developments in print mass media transforming the 20th century into a “century of images”, still and running images could reach audiences far beyond the capacity of concert rooms. Musical culture was not only heard, but also seen, and this perspective lends itself to music’s analysis through the approaches of Bildforschung and visual history,[3] introduced by the iconic turn. In this essay I will attempt to examine the nexus between the sonic and the visual in the public space using the example of musical posters produced and distributed in post-war Austria under Allied occupation, focussing on Allied musical diplomacies where power crossed spoken and written word, sound, and image.[4]

In the “land of music”, as in Germany[5], all occupation powers were eagerly promoting their arts and musical culture.[6] These transfers[7] served three goals: creating a positive image of individual Allied powers and, later, the ideological communities they represented (“socialist” versus “free” world); deconstructing the idea of Germanic superiority, anchored in the Bildungsbürgertum-based musical writing (as studies by Pamela Potter on Germany or Oliver Rathkolb on Austria itself show); and contributing to the nation-building project through enhancing Austria’s symbolic capital as Europe’s musical heartland and place of encounter of Western musical cultures. Music became a highly sensible area of Allied – and Austrian – prestige politics, and Austrian visual spaces were saturated with political and cultural posters.

The latter, while making fleeting appearances in historical research,[8] have rarely been investigated as a source sui generis on public and cultural history of Austria.[9] Present in the everyday life of many Austrians, they allow looking into the visual world and mentalities, promotion and reception patterns, language and image of musical diplomacies in Vienna and throughout the country. Designed to catch the eye of passers-by, posters were a prominent mass media and reflected agencies and goal-settings of publicly visible actors. Publishing information, overall layout, colours, print, highlighting and positioning created a “Bildakt” (Horst Bredekamp) whose public outreach could compete with the largest print media in the country. Aiming at the changes in thinking – and action (buying tickets for the concerts) –, posters had to be efficient as advertising communication and thus indicate culturally and socially transmitted codes and semiotic languages.

In the following, I will examine a selection of concert posters relating to Allied-Austrian musical interactions and their representations in the public space. Given by the Viennese Symphonic and Philharmonic Orchestras in the first post-war seasons, a series of Russian symphonic concerts (Russische Symphoniekonzerte) reveal an imagery of Russia detached from the negatively connoted Soviet hard power presence. Secondly, Allied musicians’ tours constituted objects of large-scale promotion in the media and were highly present in the Austrian public space. Finally, festivals provide another example of Austro-Allied prestige projects, from Eisenstadt and Vienna to Salzburg and Bregenz. Furthermore, a relatively stronger position that the USSR and France could claim in classical music represents a point of departure from economic, political and even media capital where the US claimed superiority. This selection of cultural overtures, while not prtending to give extensive coverage of Austro-Allied musical history, provides valuable insights into the visual representations of musical diplomacy and indicates further directions of research agenda.

The posters cited here originate from the extensive, yet often overlooked, digital collections of the Austrian National Library/ÖNB – Bildarchiv Austria and the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, and are on the whole representative of standard concert advertisement output throughout the country,[10] allowing conclusions and research perspectives of national and, potentially, European importance.

Russian Equals Musical? Public Representation of Russian Music as an Advertising and Image-Building Tool

The eight posters of the Plakatsammlung of the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus date from the 1945–1948 seasons. Printed at the smaller Walter Kubesch Verlag in 1945 and Franz Karner later (though data is incomplete) with support of the Austro-Soviet Society and, indirectly, the Soviet administration, the posters’ good printing quality is indicative of the Soviet control over money and paper. In these concerts, 19th century music, centred on Tchaikovsky, contemporary Soviet composers who had acquired international prestige, and a small number of less-known works were (re-)introduced to Austria. The posters reveal a broadly similar structure: the standard size of 85x60 cm, a contour and several textual blocks indicating the place, time, title, participators, supporting organisations and, eventually, ticket prices.

Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Plakatsammlung, P-50442.[11]

Here, the words “Russisches Symphoniekonzert” are typically placed at the centre and highlighted, sometimes with colour (as in the poster cited here), followed by the conductor and the performers, and sometimes a special occasion upon which the concerts were given (here the Red Army Day). These highlights testify of the high stakes the organisers had in public appreciation of “Russian” music and the prominent interpreters as an integral part of the Viennese soundscape. Characteristically, the composers, cited slightly below the main title, fall behind the performers who received the visual priority. In the post-liberation visual landscape, Russian music became a prominent part of Austrian concert life and its public representations: as shown by the poster below, the marketing of Russianness was not confined to Vienna.

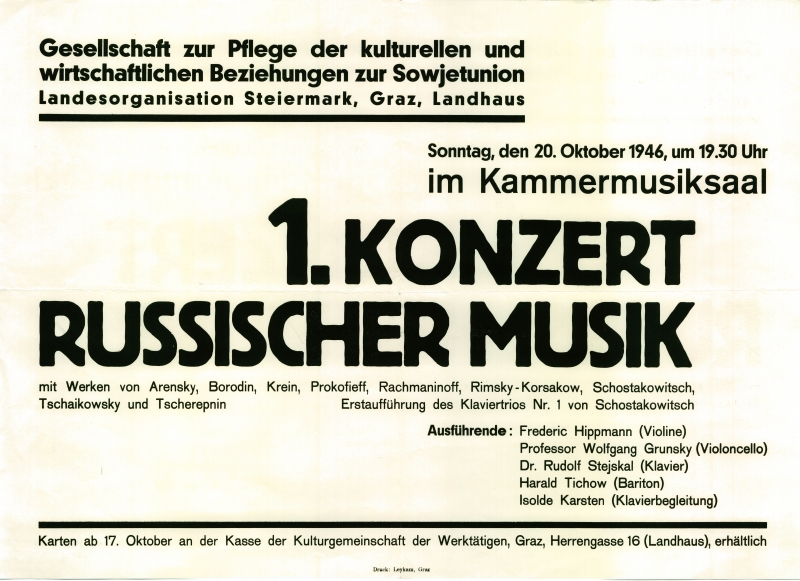

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung, PLA16319354 ; 1946/5.[12]

This “Konzert russischer Musik” took place in October 1946 at the Kammermusiksaal of the Musikverein, under the aegis of the Austro-Soviet Society and the Kulturgemeinschaft der Werktätigen. Printed at the important Leykam Verlag, the poster had a slightly smaller format (45x60 cm), yet shared the main characteristics of the Viennese productions in prominently featuring Russian music and the Society's header. After catching attention with the Russian title, the poster contains information on the composers – to which the eye would move immediately – and a separate column for the interpreters, revealing a simple and clear overall structure.

These examples indicate the existence and popularity of socially transmitted ideas of musical Russianness. Russian concerts were closely integrated into the everyday cultural landscapes of the first post-war seasons. Gaining momentum from the nationally defined stereotypes in music that dated back into the 19th century (and earlier),[13] and serving as a necessary Other in negotiations of Austria’s own identities,[14] they aimed at making Soviet presence more palatable to Austrians, while simultaneously invoking another, “domesticated” imagery of Russia’s high culture. Departing from straightforward propaganda messages, the growing prestige of Russian music constituted a clear departure from Nazism and created a sense of returning to Austrian democratic, and internationalist, musical normalcy.

Musical Ambassadors: Allied Musicians Performing in Austria

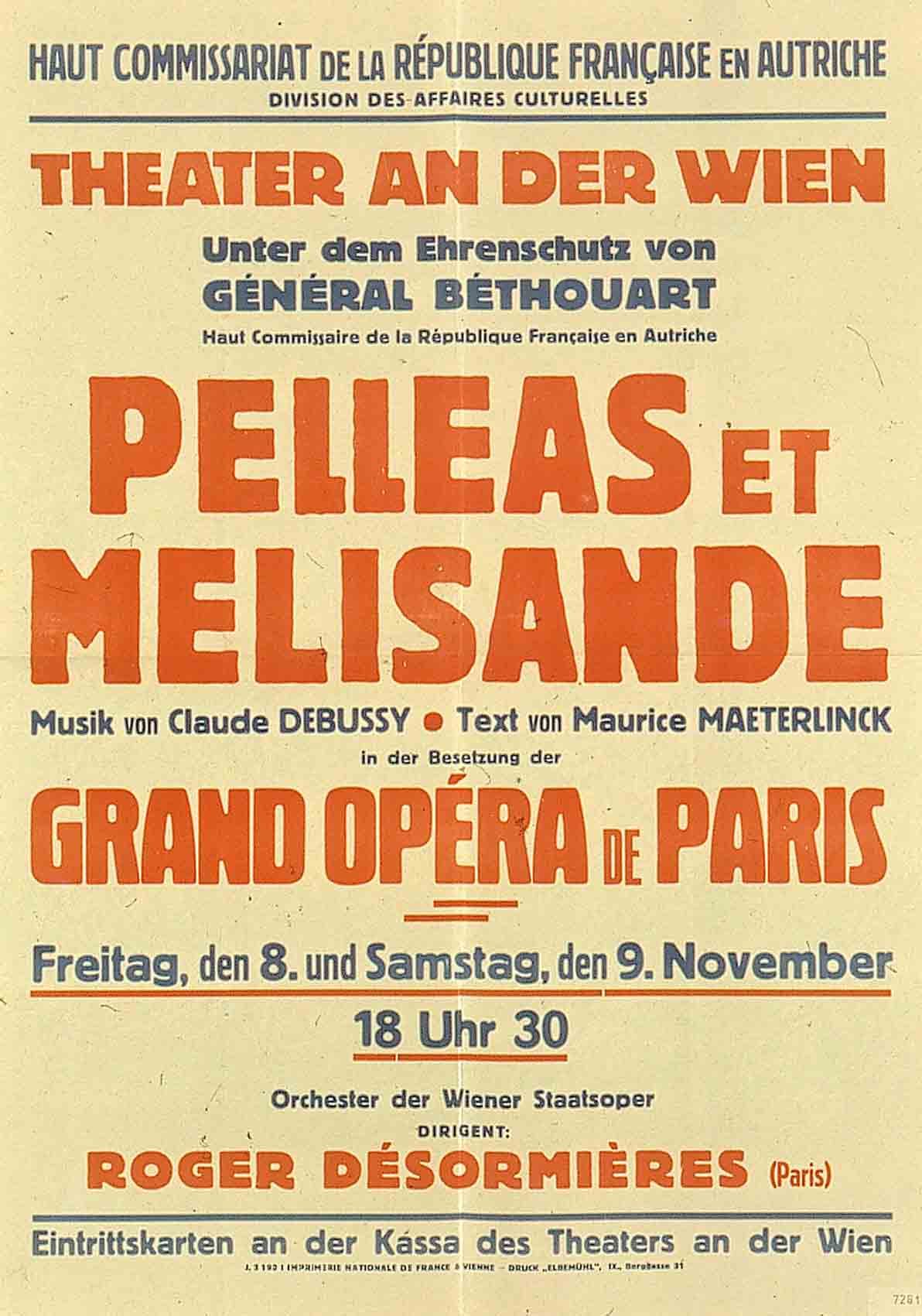

Performing musicians can potentially exert significant influence on the perception and identity-building processes, both on the concert and opera stage. Adding to opera repertoires’ transnationality, the occupation situation was conducive to increasing the share of opera music of Allied provenance in Austria. This was further facilitated by a number of guest tours, notably of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre and the Opéra-Comique, which marked the post-liberation seasons. The Parisian tour in particular received an endorsement from France’s High Commissioner Béthouart and was ultimately judged a “great success” by the French themselves[15] (for whom cultural diplomacy represented a centrepiece of occupation policies[16]).

Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Plakatsammlung, P-7281.[17]

A poster printed in 1946 at the Elbemühl Verlag (vertical, 84x58 cm) is a standard textual concert announcement. Representing the visual aspect of the French operatic diplomacy in Austria, its header stresses the support of the French Cultural Division and Béthouart. Language constitutes the main difference from other concert programmes, though the restricted vocabulary and a clear visual layout would be easily understandable for Austrians many of whom could be expected to have some command of French. Not unlike the “Russian” prints, it is in alternating two contrasting colours – red and blue – that the poster seeks to attract attention. The title, the location, the artists and the conductor are highlighted in bold red, and the designer made ample use of varying font sizes. In its simplicity, this poster is a good example of visual promotion of Allied musicians and the vigorous advances made in the first post-war seasons to conquer Austrian sympathies.

Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Plakatsammlung, P-50475.[18]

Another guest tour poster, printed for a large 1949 tour of an extensive Soviet artistic “brigade”, confirms this tendency. Its layout is very close to the “Russische Symphoniekonzerte” and the main expressive means conventionally revolve around text colour and size. Remarkably, the main eye-catcher is represented by the “only concert” (einziges Konzert) phrase, through which the Austro-Soviet society sought to advertise the event and attract a larger public. Part of the regular Austro-Soviet “weeks” and “months” campaigns, the poster structures the concert into a musical and a ballet part, with “Russian ballet” serving as another marketing tool. An orientation towards creating a positive image of Soviet Russia is notable here, as the words Soviet Artists are highlighted, whereas this adjective would be rarely used towards contemporary Russian/Soviet music in native Austrian programmes.

Promoted as specialties of the Viennese seasons, foreign tours were a frequent, if rather irregular, part of the visual culture of Austrian music life. Promoting the incoming musicians in a recognisable, clear and colourful visual language reveals a predictable, yet competent use of signposting, serving as an important means of public representation in the quotidian visual environment of Austrian cities, particularly in Vienna which was exposed to four competing cultural diplomacies. At the crossroads between Allied and Austrian prestige politics, these public events were seconded by a vibrant festival landscape taking shape in Austria, which constitutes the third mainstay of this analysis of Allied and Austrian actors’ agencies and interactions with the public.

From Eisenstadt to Bregenz: A Perspective on the Visual Culture of Austrian Festivals

Showcases of cultural prestige, festivals had been started shortly after the First World War, headed by conservative Salzburg and socialist Vienna.[19] The visual source base for Austrian festivals is far from exiguous, such by numerous photos taken by the US cultural services at Salzburg (Bildarchiv Austria/ÖNB), and posters from Vienna, Salzburg and Bregenz. Many of those reflected the run-of-the-mill production patterns close to those analysed above. As material conditions were gradually improving towards the 1950s, festival organizers began printing advertisement with wider use of coloured images and a more varied composition.

Bregenz, situated in the “golden west” of Austria, opened its own festival in 1946 in a joint initiative of the French administration and the city authorities. These Festspiele sought to attract an international public owing to the region’s healthy economy, Bregenz’ proximity to the German and Swiss borders, and its location on Lake Constance (prompting the construction of the famed Seebühne). The festival, while ultimately not rivalling that of Salzburg, quickly attained international prominence and was actively promoted within and without Austria.[20]

Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Plakatsammlung, P-25674.[21]

This 1950 poster shows most characteristic features that the city sought to promote. Printed at the Wagnersche Universitätsdruckerei in Innsbruck, it is a large-size (95x70 cm) and richly decorated, highly visual document. Through the background in marine blue, the lake is set as the stage for the theatrical and musical performances of the festival. The title “Bregenzer Festspiele" appears in red to contrast it from the programme text (dark brown), and the subtitles concentrate on the main festival events: a series of opera performances, a theatre play, and concerts of the Viennese Symphonic, the Cadets du Conservatoire de Paris, and the Vorarlberg Radio Orchestra (Vorarlberger Rundfunkorchester), as well as ballet evenings of the Vienna Opera ballet. Remarkably, this year’s French tour (Cadets) led by Claude Delvincourt was set in a standard smaller script reserved for performance details – despite being repeatedly showcased in Austria in their quality as best students of the Paris Conservatoire, they did not receive a treatment reserved to musical professionals. Ballet evenings are equally important in the context of the renaissance of Austrian academic ballet and there are first attempts to enhance their position in the festival programmes.

Festivals were gaining ascendance in the public space, and such examples as the promotion of the 1950 Bregenzer Festspiele show their growing role for Austria’s music life and tourist industry. Ushering in the years of economic prosperity, these feasts of music became highly visible events, making the study of their visual representation an interesting perspective of inquiry. Considerable means were invested in their promotion which constituted an important part of music’s visual presence both domestically and internationally.

Watching Sounds of Music? Visual Cultures of Music Promotion

Conversing with the public within a clearly distinguishable, simplified and schematised semiotic system, centred on the written text, a restricted set of highlighting tools, and growing imagery based on iconic prototypes (Gerhard Paul), concert posters constituted an important part of visual reality for many Austrians already having an interest in music, and those yet to be conquered. The former enemies were represented as cultured, musical nations, and official and semi-official endorsement aimed at demonstrating a genuine interest of the Allied administrations and local actors in establishing and reinforcing cultural ties between the Austrians and the Allies for the long peace to come. Conversely, Austria itself was promoted as a renascent musical superpower, its prestige informing Allied decisions and domestic consumption patterns.

The carefully organised composition, combination of repetitive and creative elements, and balanced signposting directed the viewer's attention, and the quotidian presence of concert posters contributed to shaping the semantic world within which many Austrians – predominantly city dwellers – were moving. Musical promoters sought to operate gradual changes in perception and popularity of music within the public sphere. Such discursive elements as constructing an associative connection between Russians and music exemplify the transmission and reinforcement of publicly received stereotypes. The Soviet-affiliated opinion-makers sought to bypass the politically determined binomial divisions through constructing an additional, musically connoted layer of Russian imagery. These tendencies could be extended to other Allies, where joint Franco-Austrian promotion campaigns represent an interesting example of the creation of such imageries, with prestige and public visibility at stake.

As this small case study shows, applying "Bildforschung" and visual culture approaches in various contexts can serve as a valuable extension of historians’ methodological tools and lead to new questionings. These are of no small importance for a number of problematiques, from (self-) representation and perception studies to the material history of media, economic, technological and semiotic aspects of cultural production and transmission within specific spatial and temporal frameworks.

[1] Essay relates to source: Musical posters in post-war Austria (1945–1950).

[2] Mecking, Sabine; Wasserloos, Yvonne (eds.), Musik-Macht-Staat. Kulturelle, soziale und politische Wandlungsprozesse in der Moderne, Göttingen 2012; Gienow-Hecht, Jessica C.E. (ed.), Music and International History in the Twentieth Century, New York 2015; Müller, Sven Oliver; Osterhammel, Jürgen; Rempe, Martin (eds.), Kommunikation im Musikleben: Harmonien und Dissonanzen im 20. Jahrhundert, Göttingen 2015; Sheperd, John; Devine, Kyle (eds.), The Routledge Reader on the Sociology of Music, New York 2015.

[3] Paul, Gerhard (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. 1900–1949, Göttingen 2009; id., BilderMACHT: Studien zur Visual History des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts, Göttingen 2013; id., “Visual History”, in: Docupedia, URL: <https://www.docupedia.de/zg/Visual_History_Version_3.0_Gerhard_Paul> (25.05.2017); Bredekamp, Horst, Theorie des Bildakts. Frankfurter Adorno-Vorlesungen 2007, Berlin 2010.

[4] Randall, Annie J. (ed.), Music, Power and Politics, New York 2005.

[5] Cf. Janik, Elizabeth, Recomposing German Music: Politics and Musical Tradition in Cold War Berlin, in: Brady, Thomas A.; Chickring, Roger (eds.), Studies in Central European Histories (XL), Leiden 2005, and works of Thobias Thacker and Andreas Linsenmann on British and French policies.

[6] Authors such as Michael Schönberg, Oliver Rathkolb, Reinhold Wagnleitner, Siegfried Beer, Margit Sandner, Klaus Eisterer, Thomas Angerer, Barbara Porpaczy, Wolfgang Mueller, Barbara Stelzl-Marx, among others, have addressed these issues; a complete historiographical review would be too extensive for this essay.

[7] Angerer, Thomas; Le Rider, Jacques (eds.), Ein Frühling, dem kein Sommer folgte? Französisch-österreichische Kulturtransfers seit 1945, Wien 1999.

[8] Sauer, Michael, “Hinweg damit!“ Plakate als historische Quellen zur Politik- und Mentalitätsgeschichte, in: Paul, Gerhard (ed.), Visual History: Ein Studienbuch, Göttingen 2006, p. 38.

[9] Existing research has largely concentrated on political propaganda: Stelzl-Marx, Barbara, Die Macht der Bilder. Sowjetische Plakate in Österreich 1945–1955, in: Bauer, Ingrid (ed.), Kunst – Kommunikation – Macht: sechster Österreichischer Zeitgeschichtetag 2003, Innsbruck 2004, pp. 63–72; Stemper, Barbara, "hallo Hallo! Hier spricht Paris!“ Zur Selbstdarstellung der französischen Besatzungsmacht in ihrer Wandzeitung in Wien 1945–1947, Mag. Dipl.-Arb., Wien 2013. The “moving image”, falling beyond the scope of this essay, was equally instrumentalised: Moser, Karin (ed.), Besetzte Bilder: Film, Kultur und Propaganda in Österreich 1945–1955, Vienna: Wien 2005.

[10] URL: <https://www.bildarchivaustria.at/>, <http://www.wienbibliothek.at/bestaende-sammlungen/plakatsammlung> (12.03.2018). Large poster collections can be consulted in situ at the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, the Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv, the Innsbrucker Stadtarchiv, the Salzburger Landesarchiv or the ORF Archiv, Wien, and others.

[11] Source: II. Russisches Symphoniekonzert. Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, URL: <http://opac.obvsg.at/opac_help/WBR-bildobjekt.html?AC10571130-4201> (12.03.2018).

[12] Konzert russischer Musik. ÖNB/Bildarchiv Austria, URL: <http://data.onb.ac.at/rec/baa15894894> (12.03.2018).

[13] Cf. Leerssen, Joep, Romanticism, Music, Nationalism, in: Nations and Nationalism 20 (2014), pp. 606–627; Lajosi, Kristina, National Stereotypes and Music, in: ibid., pp. 628–645.

[14] Cf. Fauser, Annegret, The Politics of Musical Identity: Selected Essays, Aldershot 2015, p. XII.

[15] Béthouart, Marie-Antoine, La bataille pour l’Autriche, Paris 1966, p. 223.

[16] Porpaczy, Barbara, Frankreich-Österreich 1945–1960: Kulturpolitik und Identität, Wien 2002.

[17] Pelléas et Mélisande, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, URL: <http://opac.obvsg.at/opac_help/WBR-bildobjekt.html?AC10604057-4201> (12.03.2018).

[18] Einziges Konzert: Sowjetische Künstler aus Moskau und Leningrad, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, URL: <http://opac.obvsg.at/opac_help/WBR-bildobjekt.html?AC10571163-4201> (12.03.2018).

[19] Burri, Michael, Austrian Festival Missions after 1918: The Vienna Music Festival and the Long Shadow of Salzburg, Austrian History Yearbook 47 (2016), pp. 147–166.

[20] Bösch-Niederer, Annemarie, Kultureller Aufbruch. Vorarlbergs Musikleben nach 1945, in: Nachbaur, Ulrich; Niederstätter, Alois (eds.), Aufbruch in eine neue Zeit. Vorarlberger Almanach zum Jubiläumsjahr 2005, Bregenz 2006, pp. 294–295.

[21] Bregenzer Festspiele, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, URL: <http://opac.obvsg.at/opac_help/WBR-bildobjekt.html?AC10592498-4201> (12.03.2018).

Bibliography

Angerer, Thomas; Le Rider, Jacques (eds.), Ein Frühling, dem kein Sommer folgte? Französisch-österreichische Kulturtransfers seit 1945, Wien 1999.

Janik, Elizabeth, Recomposing German Music: Politics and Musical Tradition in Cold War Berlin, Boston 2005.

Mueller, Wolfgang, Die sowjetische Besatzung in Österreich 1945–1955 und ihre politische Mission, Wien 2005.

Paul, Gerhard, BilderMACHT: Studien zur Visual History des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts, Göttingen 2013.

Zalfen, Sarah; Müller, Sven (eds.), Besatzungsmacht Musik: Zur Musik-und Emotionsgeschichte im Zeitalter der Weltkriege (1914–1949), Bielefeld 2012.